I’ve expanded a bit on my earlier example of simulating ripples on water in WPF. Last time, I started a ripple by inducing a single peak value into a grid of points and then watching the ripples propagate.

Full source code available at: http://wavesim.codeplex.com

This time, we go much further, inducing peaks at random intervals to simulate raindrops falling on a liquid surface. The underlying algorithm for propagating the ripples is identical to last time—calculating new height values for every point in a 2D mesh, using a basic filtering/smoothing algorithm.

To see the final result right away, you can download/run the WPF application from here. As before, you can use the mouse wheel to zoom in/out, while the simulation is running.

I’ve updated the GUI to include a few knobs that you can play with. The three sliders that control the raindrops are:

- Num Drops – Controls how fast the drops are falling. For starters, the average time between raindrops is 35ms. The slider allows changing the frequency, such that the time between drops ranges from 1ms to 1000ms. (On average)

- Drop Strength – Controls how deep the drop falls, which impacts the amplitude of the resulting ripples. Defaults to creating a drop that goes 3.0 units deep, with a range of [0,15]. (Grid is 250×250 units).

- Drop Size – The diameter of the drop that comes down. (Actually, drops are square, so this value is the length of one side of the square). Defaults to 1, range is [1,6].

To start the animation, with the default values, click on the Start Rain button. You’ll get a nice/natural animated scene, with raindrops falling on the water. (On my graphics card, at least, this results in an animation that feels close to real-time—this may not be true on slower/faster cards).

The next thing to try playing with is the Num Drops setting, leaving everything else the same. The raindrop frequency will increase as you move the slider, and you’ll a much more agitated surface, since the ripples don’t have enough time to damp.

Now try turning the Num Drops setting back down low and turn up the Drop Size setting. Now you’ll get nice fat drops that create pretty good-size ripples.

Finally, set Drop Size back down again and try playing with the Drop Strength setting. You’ll simulate stronger drops, as we create much deeper craters for each drop initially. Also notice the little tower of water the jumps up as the first visual indication of a drop.

You can obviously play with all three of the settings at the same time. Doing so, you can easily get a pretty crazy bathtub effect, as the waves just get larger and larger.

Use of the Wave button is left as an exercise to the reader. It basically introduces a deep channel across the entire wave mesh, which results in a fairly large wave that propagates out in both directions.

One interesting thing to note about the wave is that you’ll see the existing ripples bend around the wave and continue propagating outward. Also note that, because we add all amplitudes to existing point heights, new drops that fall on the wave will be at the proper height, relative to the current wave height.

Ok, I can’t resist. Here’s a screencap of the Wave in action.

Below is the WPF code that I used for the simulation. As before, the three parts are: a) the static XAML that sets up the window; b) the code-behind for Window1, which runs the Rendering loop and c) the WaveGrid class, which does the actual simulation and contains the two point buffers.

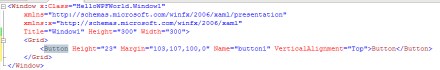

Here is the XAML code for the main window, nothing too spectacular:

<Window x:Class="WaveSim.Window1"

xmlns="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml/presentation"

xmlns:x="http://schemas.microsoft.com/winfx/2006/xaml"

Title="Window1" Height="679.023" Width="812.646"

MouseWheel="Window_MouseWheel">

<Grid Name="grid1" Height="618.12" Width="759.015">

<Grid.RowDefinitions>

<RowDefinition Height="76*" />

<RowDefinition Height="542.12*" />

</Grid.RowDefinitions>

<Button HorizontalAlignment="Right" Margin="0,11.778,115,0" Name="btnStart" Width="75" Click="btnStart_Click" Height="22.649" VerticalAlignment="Top">Start Rain</Button>

<Viewport3D Name="viewport3D1" Grid.Row="1">

<Viewport3D.Camera>

<PerspectiveCamera x:Name="camMain" Position="255 38.5 255" LookDirection="-130 -40 -130" FarPlaneDistance="450" UpDirection="0,1,0" NearPlaneDistance="1" FieldOfView="70">

</PerspectiveCamera>

</Viewport3D.Camera>

<ModelVisual3D x:Name="vis3DLighting">

<ModelVisual3D.Content>

<DirectionalLight x:Name="dirLightMain" Direction="2, -2, 0"/>

</ModelVisual3D.Content>

</ModelVisual3D>

<ModelVisual3D>

<ModelVisual3D.Content>

<DirectionalLight Direction="0, -2, 2"/>

</ModelVisual3D.Content>

</ModelVisual3D>

<ModelVisual3D>

<ModelVisual3D.Content>

<GeometryModel3D x:Name="gmodMain">

<GeometryModel3D.Geometry>

<MeshGeometry3D x:Name="meshMain" >

</MeshGeometry3D>

</GeometryModel3D.Geometry>

<GeometryModel3D.Material>

<MaterialGroup>

<DiffuseMaterial x:Name="matDiffuseMain">

<DiffuseMaterial.Brush>

<SolidColorBrush Color="DarkBlue"/>

</DiffuseMaterial.Brush>

</DiffuseMaterial>

<SpecularMaterial SpecularPower="24">

<SpecularMaterial.Brush>

<SolidColorBrush Color="LightBlue"/>

</SpecularMaterial.Brush>

</SpecularMaterial>

</MaterialGroup>

</GeometryModel3D.Material>

</GeometryModel3D>

</ModelVisual3D.Content>

</ModelVisual3D>

</Viewport3D>

<Slider Margin="0,13.596,198,0" Name="slidPeakHeight" ValueChanged="slidPeakHeight_ValueChanged" Minimum="0" Maximum="15" HorizontalAlignment="Right" Width="167.256" Height="20.831" VerticalAlignment="Top" />

<Label Margin="286,11.964,0,36.083" Name="lblDropDepth" HorizontalAlignment="Left" Width="89.015">Drop Strength</Label>

<Slider Name="slidNumDrops" HorizontalAlignment="Left" Margin="111,15.452,0,0" Maximum="1000" Minimum="1" Width="167.256" ValueChanged="slidNumDrops_ValueChanged" Height="20.831" VerticalAlignment="Top" />

<Label HorizontalAlignment="Left" Margin="12,13.596,0,34.451" Name="label1" Width="89">Num Drops</Label>

<Button HorizontalAlignment="Right" Margin="0,11.963,19,0" Name="btnWave" Width="75" Click="btnWave_Click" Height="22.649" VerticalAlignment="Top">Wave !</Button>

<Slider Height="20.831" HorizontalAlignment="Left" Margin="111,0,0,5.266" Maximum="6" Minimum="1" Name="slidDropSize" VerticalAlignment="Bottom" Width="167.256" ValueChanged="slidDropSize_ValueChanged"/>

<Label Height="27.953" HorizontalAlignment="Left" Margin="12,0,0,0" Name="label2" VerticalAlignment="Bottom" Width="89">Drop Size</Label>

</Grid>

</Window>

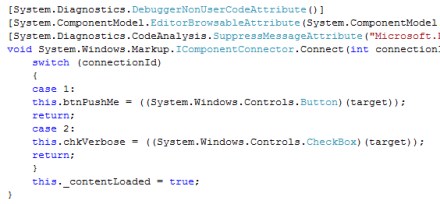

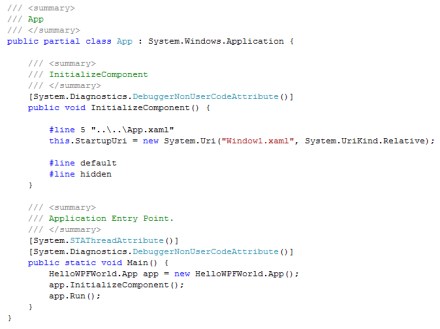

Here is the Window1.xaml.cs code. Some things to take note of:

- We’re no longer setting peaks in the center of the grid, but calling SetRandomPeak to induce each raindrop

- As before, we’re using the CompositionTarget_Rendering event handler as our main rendering loop. During the loop, we induce new raindrops, tell the grid to process the point mesh (propagating waves) and we then reattach the new point grid to our MeshGeometry3D

- Note that we calculate the number of drops to induce by first calculating how many drops we should drop each time we visit this loop (should be moved outside the loop). We induce points for the integer portion of this number and then use the fractional part as a % chance of dropping one more point.

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Windows;

using System.Windows.Controls;

using System.Windows.Data;

using System.Windows.Documents;

using System.Windows.Input;

using System.Windows.Media;

using System.Windows.Media.Media3D;

using System.Windows.Media.Imaging;

using System.Windows.Navigation;

using System.Windows.Shapes;

using System.Windows.Threading;

namespace WaveSim

{

/// <summary>

/// Interaction logic for Window1.xaml

/// </summary>

public partial class Window1 : Window

{

private Vector3D zoomDelta;

private WaveGrid _grid;

private bool _rendering;

private double _lastTimeRendered;

private Random _rnd = new Random(1234);

// Raindrop parameters. Negative amplitude causes little tower of

// water to jump up vertically in the instant after the drop hits.

private double _splashAmplitude; // Average height (depth, since negative) of raindrop splashes.

private double _splashDelta = 1.0; // Actual splash height is Ampl +/- Delta (random)

private double _raindropPeriodInMS;

private double _waveHeight = 15.0;

private int _dropSize;

// Values to try:

// GridSize=20, RenderPeriod=125

// GridSize=50, RenderPeriod=50

private const int GridSize = 250; //50;

private const double RenderPeriodInMS = 60; //50;

public Window1()

{

InitializeComponent();

_splashAmplitude = -3.0;

slidPeakHeight.Value = -1.0 * _splashAmplitude;

_raindropPeriodInMS = 35.0;

slidNumDrops.Value = 1.0 / (_raindropPeriodInMS / 1000.0);

_dropSize = 1;

slidDropSize.Value = _dropSize;

// Set up the grid

_grid = new WaveGrid(GridSize);

meshMain.Positions = _grid.Points;

meshMain.TriangleIndices = _grid.TriangleIndices;

// On each WheelMouse change, we zoom in/out a particular % of the original distance

const double ZoomPctEachWheelChange = 0.02;

zoomDelta = Vector3D.Multiply(ZoomPctEachWheelChange, camMain.LookDirection);

}

private void Window_MouseWheel(object sender, MouseWheelEventArgs e)

{

if (e.Delta > 0)

// Zoom in

camMain.Position = Point3D.Add(camMain.Position, zoomDelta);

else

// Zoom out

camMain.Position = Point3D.Subtract(camMain.Position, zoomDelta);

}

// Start/stop animation

private void btnStart_Click(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

if (!_rendering)

{

//_grid = new WaveGrid(GridSize); // New grid allows buffer reset

_grid.FlattenGrid();

meshMain.Positions = _grid.Points;

_lastTimeRendered = 0.0;

CompositionTarget.Rendering += new EventHandler(CompositionTarget_Rendering);

btnStart.Content = "Stop";

_rendering = true;

}

else

{

CompositionTarget.Rendering -= new EventHandler(CompositionTarget_Rendering);

btnStart.Content = "Start";

_rendering = false;

}

}

void CompositionTarget_Rendering(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

RenderingEventArgs rargs = (RenderingEventArgs)e;

if ((rargs.RenderingTime.TotalMilliseconds - _lastTimeRendered) > RenderPeriodInMS)

{

// Unhook Positions collection from our mesh, for performance

// (see http://blogs.msdn.com/timothyc/archive/2006/08/31/734308.aspx)

meshMain.Positions = null;

// Do the next iteration on the water grid, propagating waves

double NumDropsThisTime = RenderPeriodInMS / _raindropPeriodInMS;

// Result at this point for number of drops is something like

// 2.25. We'll induce integer portion (e.g. 2 drops), then

// 25% chance for 3rd drop.

int NumDrops = (int)NumDropsThisTime; // trunc

for (int i = 0; i < NumDrops; i++)

_grid.SetRandomPeak(_splashAmplitude, _splashDelta, _dropSize);

if ((NumDropsThisTime - NumDrops) > 0)

{

double DropChance = NumDropsThisTime - NumDrops;

if (_rnd.NextDouble() <= DropChance)

_grid.SetRandomPeak(_splashAmplitude, _splashDelta, _dropSize);

}

_grid.ProcessWater();

// Then update our mesh to use new Z values

meshMain.Positions = _grid.Points;

_lastTimeRendered = rargs.RenderingTime.TotalMilliseconds;

}

}

private void slidPeakHeight_ValueChanged(object sender, RoutedPropertyChangedEventArgs<double> e)

{

// Slider runs [0,30], so our amplitude runs [-30,0].

// Negative amplitude is desirable because we see little towers of

// water as each drop bloops in.

_splashAmplitude = -1.0 * slidPeakHeight.Value;

}

private void slidNumDrops_ValueChanged(object sender, RoutedPropertyChangedEventArgs<double> e)

{

// Slider runs from [1,1000], with 1000 representing more drops (1 every ms) and

// 1 representing fewer (1 ever 1000 ms). This is to make slider seem natural

// to user. But we need to invert it, to get actual period (ms)

_raindropPeriodInMS = (1.0 / slidNumDrops.Value) * 1000.0;

}

private void btnWave_Click(object sender, RoutedEventArgs e)

{

_grid.InduceWave(_waveHeight);

}

private void slidDropSize_ValueChanged(object sender, RoutedPropertyChangedEventArgs<double> e)

{

_dropSize = (int)slidDropSize.Value;

}

}

}

Finally, here is the updated code for the WaveGrid class. Things to note:

- We’ve replaced SetCenterPeak with SetRandomPeak, which does the “dropping”

- The crazy wave is induced in InduceWave

- I’ve added a FlattenGrid function, to calm things down

using System;

using System.Collections.Generic;

using System.Diagnostics;

using System.Linq;

using System.Text;

using System.Windows.Media;

using System.Windows.Media.Media3D;

namespace WaveSim

{

class WaveGrid

{

// Constants

const int MinDimension = 5;

const double Damping = 0.96; // SAVE: 0.96

const double SmoothingFactor = 2.0; // Gives more weight to smoothing than to velocity

// Private member data

private Point3DCollection _ptBuffer1;

private Point3DCollection _ptBuffer2;

private Int32Collection _triangleIndices;

private Random _rnd = new Random(48339);

private int _dimension;

// Pointers to which buffers contain:

// – Current: Most recent data

// – Old: Earlier data

// These two pointers will swap, pointing to ptBuffer1/ptBuffer2 as we cycle the buffers

private Point3DCollection _currBuffer;

private Point3DCollection _oldBuffer;

///

/// Construct new grid of a given dimension

///

///

public WaveGrid(int Dimension)

{

if (Dimension < MinDimension)

throw new ApplicationException(string.Format("Dimension must be at least {0}", MinDimension.ToString()));

_ptBuffer1 = new Point3DCollection(Dimension * Dimension);

_ptBuffer2 = new Point3DCollection(Dimension * Dimension);

_triangleIndices = new Int32Collection((Dimension - 1) * (Dimension - 1) * 2);

_dimension = Dimension;

InitializePointsAndTriangles();

_currBuffer = _ptBuffer2;

_oldBuffer = _ptBuffer1;

}

///

/// Access to underlying grid data

///

public Point3DCollection Points

{

get { return _currBuffer; }

}

///

/// Access to underlying triangle index collection

///

public Int32Collection TriangleIndices

{

get { return _triangleIndices; }

}

///

/// Dimension of grid–same dimension for both X & Y

///

public int Dimension

{

get { return _dimension; }

}

///

/// Induce new disturbance in grid at random location. Height is

/// PeakValue +/- Delta. (Random value in this range)

///

///

Base height of new peak in grid

///

Max amount to add/sub from BasePeakValue to get actual value

///

# pixels wide, [1,4]

public void SetRandomPeak(double BasePeakValue, double Delta, int PeakWidth)

{

if ((PeakWidth < 1) || (PeakWidth > (_dimension / 2)))

throw new ApplicationException(“WaveGrid.SetRandomPeak: PeakWidth param must be <= half the dimension");

int row = (int)(_rnd.NextDouble() * ((double)_dimension - 1.0));

int col = (int)(_rnd.NextDouble() * ((double)_dimension - 1.0));

// When caller specifies 0.0 peak, we assume always 0.0, so don't add delta

if (BasePeakValue == 0.0)

Delta = 0.0;

double PeakValue = BasePeakValue + (_rnd.NextDouble() * 2 * Delta) - Delta;

// row/col will be used for top-left corner. But adjust, if that

// puts us out of the grid.

if ((row + (PeakWidth - 1)) > (_dimension – 1))

row = _dimension – PeakWidth;

if ((col + (PeakWidth – 1)) > (_dimension – 1))

col = _dimension – PeakWidth;

// Change data

for (int ir = row; ir < (row + PeakWidth); ir++)

for (int ic = col; ic < (col + PeakWidth); ic++)

{

Point3D pt = _oldBuffer[(ir * _dimension) + ic];

pt.Y = pt.Y + (int)PeakValue;

_oldBuffer[(ir * _dimension) + ic] = pt;

}

}

///

/// Induce wave along back edge of grid by creating large

/// wall.

///

///

public void InduceWave(double WaveHeight)

{

if (_dimension >= 15)

{

// Just set height of a few rows of points (in middle of grid)

int NumRows = 20;

//double[] SineCoeffs = new double[10] { 0.156, 0.309, 0.454, 0.588, 0.707, 0.809, 0.891, 0.951, 0.988, 1.0 };

Point3D pt;

int StartRow = _dimension / 2;

for (int i = (StartRow – 1) * _dimension; i < (_dimension * (StartRow + NumRows)); i++)

{

int RowNum = (i / _dimension) + StartRow;

pt = _oldBuffer[i];

//pt.Y = pt.Y + (WaveHeight * SineCoeffs[RowNum]);

pt.Y = pt.Y + WaveHeight ;

_oldBuffer[i] = pt;

}

}

}

///

/// Leave buffers in place, but change notation of which one is most recent

///

private void SwapBuffers()

{

Point3DCollection temp = _currBuffer;

_currBuffer = _oldBuffer;

_oldBuffer = temp;

}

///

/// Clear out points/triangles and regenerates

///

///

private void InitializePointsAndTriangles()

{

_ptBuffer1.Clear();

_ptBuffer2.Clear();

_triangleIndices.Clear();

int nCurrIndex = 0; // March through 1-D arrays

for (int row = 0; row < _dimension; row++)

{

for (int col = 0; col < _dimension; col++)

{

// In grid, X/Y values are just row/col numbers

_ptBuffer1.Add(new Point3D(col, 0.0, row));

// Completing new square, add 2 triangles

if ((row > 0) && (col > 0))

{

// Triangle 1

_triangleIndices.Add(nCurrIndex – _dimension – 1);

_triangleIndices.Add(nCurrIndex);

_triangleIndices.Add(nCurrIndex – _dimension);

// Triangle 2

_triangleIndices.Add(nCurrIndex – _dimension – 1);

_triangleIndices.Add(nCurrIndex – 1);

_triangleIndices.Add(nCurrIndex);

}

nCurrIndex++;

}

}

// 2nd buffer exists only to have 2nd set of Z values

_ptBuffer2 = _ptBuffer1.Clone();

}

///

/// Set height of all points in mesh to 0.0. Also resets buffers to

/// original state.

///

public void FlattenGrid()

{

Point3D pt;

for (int i = 0; i < (_dimension * _dimension); i++)

{

pt = _ptBuffer1[i];

pt.Y = 0.0;

_ptBuffer1[i] = pt;

}

_ptBuffer2 = _ptBuffer1.Clone();

_currBuffer = _ptBuffer2;

_oldBuffer = _ptBuffer1;

}

///

/// Determine next state of entire grid, based on previous two states.

/// This will have the effect of propagating ripples outward.

///

public void ProcessWater()

{

// Note that we write into old buffer, which will then become our

// “current” buffer, and current will become old.

// I.e. What starts out in _currBuffer shifts into _oldBuffer and we

// write new data into _currBuffer. But because we just swap pointers,

// we don’t have to actually move data around.

// When calculating data, we don’t generate data for the cells around

// the edge of the grid, because data smoothing looks at all adjacent

// cells. So instead of running [0,n-1], we run [1,n-2].

double velocity; // Rate of change from old to current

double smoothed; // Smoothed by adjacent cells

double newHeight;

int neighbors;

int nPtIndex = 0; // Index that marches through 1-D point array

// Remember that Y value is the height (the value that we’re animating)

for (int row = 0; row < _dimension; row++)

{

for (int col = 0; col < _dimension; col++)

{

velocity = -1.0 * _oldBuffer[nPtIndex].Y; // row, col

smoothed = 0.0;

neighbors = 0;

if (row > 0) // row-1, col

{

smoothed += _currBuffer[nPtIndex – _dimension].Y;

neighbors++;

}

if (row < (_dimension - 1)) // row+1, col

{

smoothed += _currBuffer[nPtIndex + _dimension].Y;

neighbors++;

}

if (col > 0) // row, col-1

{

smoothed += _currBuffer[nPtIndex – 1].Y;

neighbors++;

}

if (col < (_dimension - 1)) // row, col+1

{

smoothed += _currBuffer[nPtIndex + 1].Y;

neighbors++;

}

// Will always have at least 2 neighbors

smoothed /= (double)neighbors;

// New height is combination of smoothing and velocity

newHeight = smoothed * SmoothingFactor + velocity;

// Damping

newHeight = newHeight * Damping;

// We write new data to old buffer

Point3D pt = _oldBuffer[nPtIndex];

pt.Y = newHeight; // row, col

_oldBuffer[nPtIndex] = pt;

nPtIndex++;

}

}

SwapBuffers();

}

}

}

[/sourcecode]

That’s basically it. If anyone is interested in getting the source code, leave a comment and I’ll take the trouble to post it somewhere.